For the Pasinaya CCP Open House Festival 2022: Sana All Lumilikha, Lumalaya, the CCP Visual Arts and Museum Division invited National Artist BenCab and his fellow CCP Thirteen Artists Awardees (TAA) Noel Soler Cuizon, Imelda Cajipe Endaya, Brenda V. Fajardo, Egai Talusan Fernandez, Karen Ocampo Flores, Renato Habulan, Junyee, Jose Tence Ruiz, and Phyllis Zaballero to share their firsthand experiences of the EDSA People Power Revolution in 1986 along with their artworks and archival photos.

BenCab, People Power '86 II, Acrylic on paper, 1986

BenCab, People Power '86 II, Acrylic on paper, 1986“During the Martial Law years before I came back to the Philippines in late 1985, I continued to work on paintings and prints with social commentary. When Ninoy Aquino’s assassination in 1983 triggered street protests, I had a feeling it was the start of the end of the dictatorship and I wanted to be in the Philippines to witness history. By February 1986, I was in Baguio, having just come home from London a few months before, after being away for 13 years. I felt compelled to be part of the groundswell of protests against the Marcos dictatorship. When I learned that people were gathering on EDSA, I went down to Manila and joined them together with some friends. The mood was tense as we didn’t know how long we would be there and if the military would attack the crowd. In spite of that, people were friendly and shared food and drinks. We were tuned in to Radio Veritas and when we heard that the Marcoses had left Malacañan Palace, we drove there. We saw the mob was rowdy so I just picked up some barbed wire as a souvenir which I used in an artwork later. It was a feeling of euphoria and jubilation—I felt good to be a part of it.”

—BenCab, National Artist, TAA year: 1990

Imelda Cajipe Endaya, Bigkis ng Pagkakaisa, 1985

Imelda Cajipe Endaya, Bigkis ng Pagkakaisa, 1985“The EDSA People Power Revolution did not happen in one day. It was a build up with a tipping point in 1983 dahil hindi naman iyon nangyari ng biglaan. Tatlong taon from 1983 to 1986 na malayo sa panahon ngayon - walang social media noon. The tipping point, as you know in history, was the assassination of Ninoy Aquino wherein all the sectors united, lahat ng kulay nagkasama-sama dahil sawang-sawa na sila sa mga pangyayari, sa mga pang-aapi, sa dami ng namatay, at sa pang-aabuso.

Artist ako at may anak akong maliliit noon, tatlo sila, na hindi ko maiwan at masama - full time artist at full time nanay, hindi mapaghihiwalay iyon. Kung makakalabas ako, sumasama ako sa urban poor group sa Makati kung saan pinag-uusapan ang history at papaano labanan ang diktadura. Mapalad akong hindi ako nakaranas ng masamang karanasan gaya ng mga kasama ko na nakulong. Nag-concentrate ako noon sa art, sa sining pero nandoon pa rin ang takot. Sa aking artworks, makikita dito ang mga simbolo na nagpapahiwatig ng galit at takot nung panahon na iyon lalo na sa mga kababaihan. Mga kababaihan na kailangan na maglakas-loob na lumabas ng tahanan para makatulong sa pagbabago ng lipunan. Maraming nasulat na babasahin, tula, awit at mga napinta na kung makita [ng gobyerno] ay pwede ka ng ikulong. Napakahirap noon kahit hindi kahina-hinala pwede kang damputin.

Halos araw-araw noon Pebrero hanggang February 25, [1986] nag-kacarpooling kami papunta ng EDSA, na nalaman namin mula sa mosquito press. Magkakasama kami ni Sister Ida, Brenda [Fajardo], at Ana Fer sa pagmamartsa sa kalye. Nakakatuwa parang lahat ng tao pamilya mo. Doon sa makikita mo sa tapat yung mga sundalo na bibigyan ng bulaklak at pagkakain mag-shashare lahat. Pagkatapos ng EDSA People Power at nawala na si Marcos, sumaya ang mga tao pero ang problemang iniwan niya nandyan pa rin. Napakatagal ko rin nagulantang tungkol sa demokrasya, freedom, at hustisya kung saan yung number one oppressor [si Marcos] nawala pero yung problemang iniwan niya nandyan pa rin at may mga nagmana.

Sa panahon ngayon mga kabataan, pag-aralan ang kasaysayan at katotohan. Maging makatotoo, maging sinsero, at pagtulungan natin ang pagbabago para sa hustisya.”

—Imelda Cajipe Endaya, TAA Year: 1990

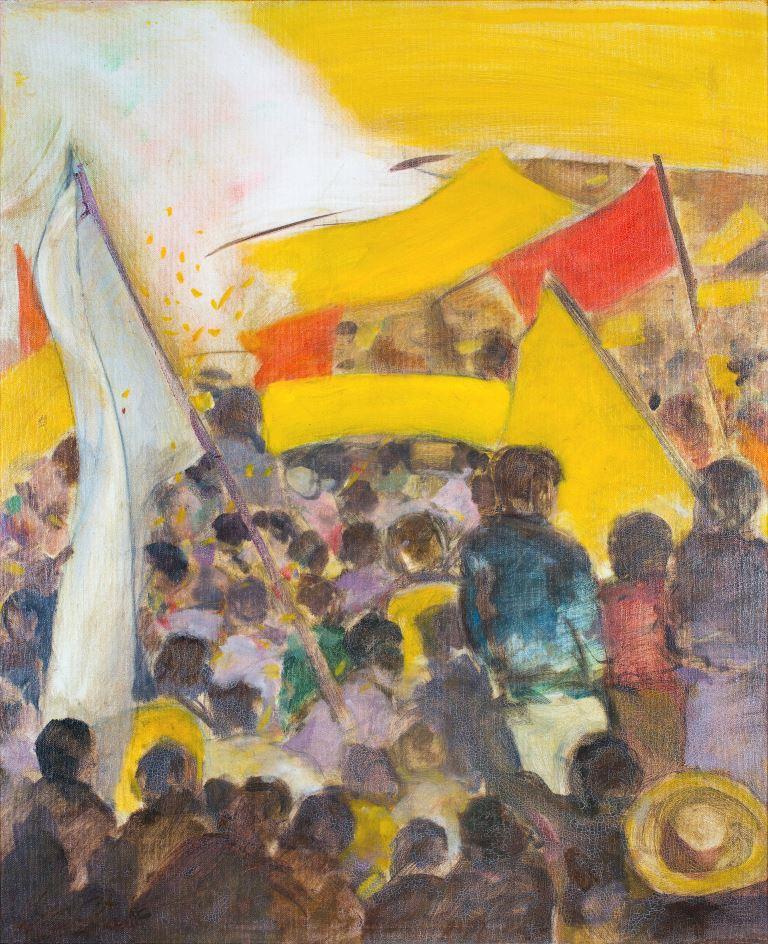

Bato bato pik sa EDSA series, Acrylic on canvas, 1986-87

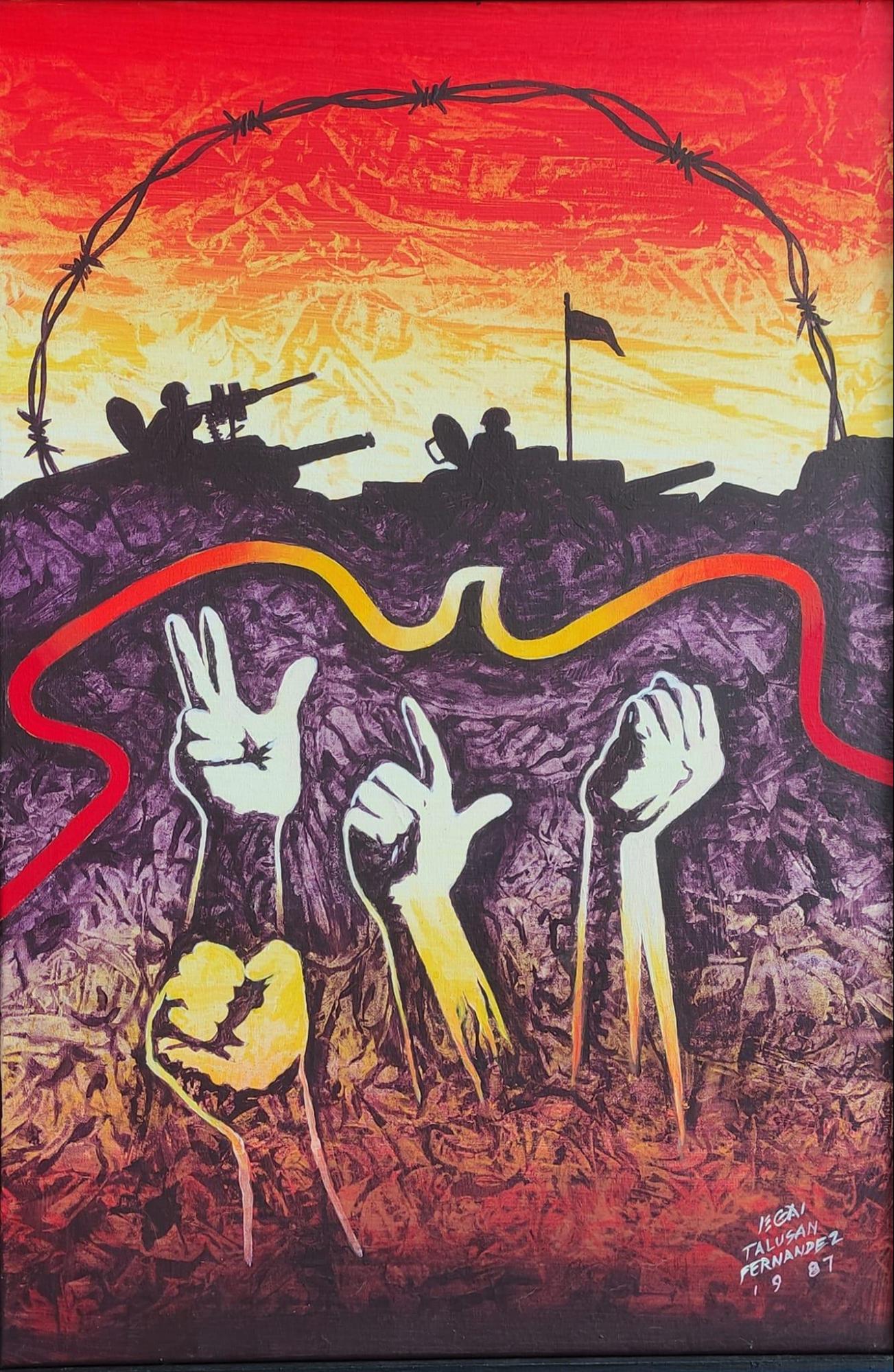

Bato bato pik sa EDSA series, Acrylic on canvas, 1986-87“Umuwi ako mula Paris nung late 1981 sa pag-aakalang na-lift na ang Martial Law. Sa papel lang pala at may Presidential Decree 868 pa na batayan para i-sensor ang script ng play o pelikula. Hindi malayong lahat ng sangay ng sining ay madadale din. Mismong "freedom of expression" ay wala na kaya nabuo ang "Free the Artists" movement. Lahat ng larangan ng sining ay nanindigan laban sa pang aabuso ng police power. Nuong assassination ni Ninoy ay gumulong ang JAJA (Justice for Aquino Justice for All) at ang free the Artist movement ay napormalize bilang CAP, Concern Artists of the Philippines. Napilitan na magdaos ng snap election at ng mag-walk out ang comelec 35 dahil sa pandaraya na naghanap. Gumulong din ang civil disobedience, boycotting the businesses ng mga crony. Nang nagtago sa Camp Crame sina Ramos at Enrile dahil ipapahuli sila ni Marcos dahil nabuking yun planong Kudeta. Nang nanawagan si Cardinal Sin sa publiko na protektahan sila ay unti unti dumami ang tao sa EDSA. Kahit ako ay nag-punta at nagmasid at nakagawa ng ilang sketches... Malinaw na pag nagsama-sama ang lumalaban para sa kalayaan ito ay magiging matagumpay.”

—Egai Talusan Fernandez, TAA Year: 1990

“In 1983, I was in Japan when I heard about Ninoy Aquino’s death which made me very nervous. I was not in my country when these difficulties were coming up though I was still able to make artworks. When I returned during Martial Law, artists were full of work, creating works on the streets in theater and through murals. Some friends were tortured so they told us these stories and shared what they were feeling. They expressed their hard feelings and we were there to listen to them at the same time we were able to grasp what they were experiencing and transferred it into our artworks. There were hard times because many were hurt, persecuted, and abused.

During the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution, I was at home monitoring what was going on in the media. It was exciting and nerve-wracking because no one knew how it would end. It was an exciting moment because it was a historical event, a revolution. It was a moment when many things were being revealed after many years where there were so many difficult truths and realities not told to us, the public.

After EDSA, we heard so many unbelievable narratives of tortures and unthinkable things done by Filipinos to their fellow Filipinos. It hurts to learn that they can do that to their fellow citizens. Now, it is very difficult because there are so many who are trying to revise history. There are people who are trying to deny what happened so that the younger generations will have a distorted idea of what was really happening. This is why it is important for artists to document this and also for those who experienced torture to express their paint through art such as a poem or a picture so that truth will prevail.

To the youth, read and research about what really happened during Martial Law. If we want to revise history, it is in our hands - to revise not what happened but to change the course of history moving forward. So act so you can contribute to change in the future but how can you change the future if you don’t know what happened in the past? Let’s be careful to read and learn the facts so that we don’t repeat what happened. Huwag basta basta maniwala! This is how we safeguard history. We must act. We must fight for the truth. We must not be afraid.”

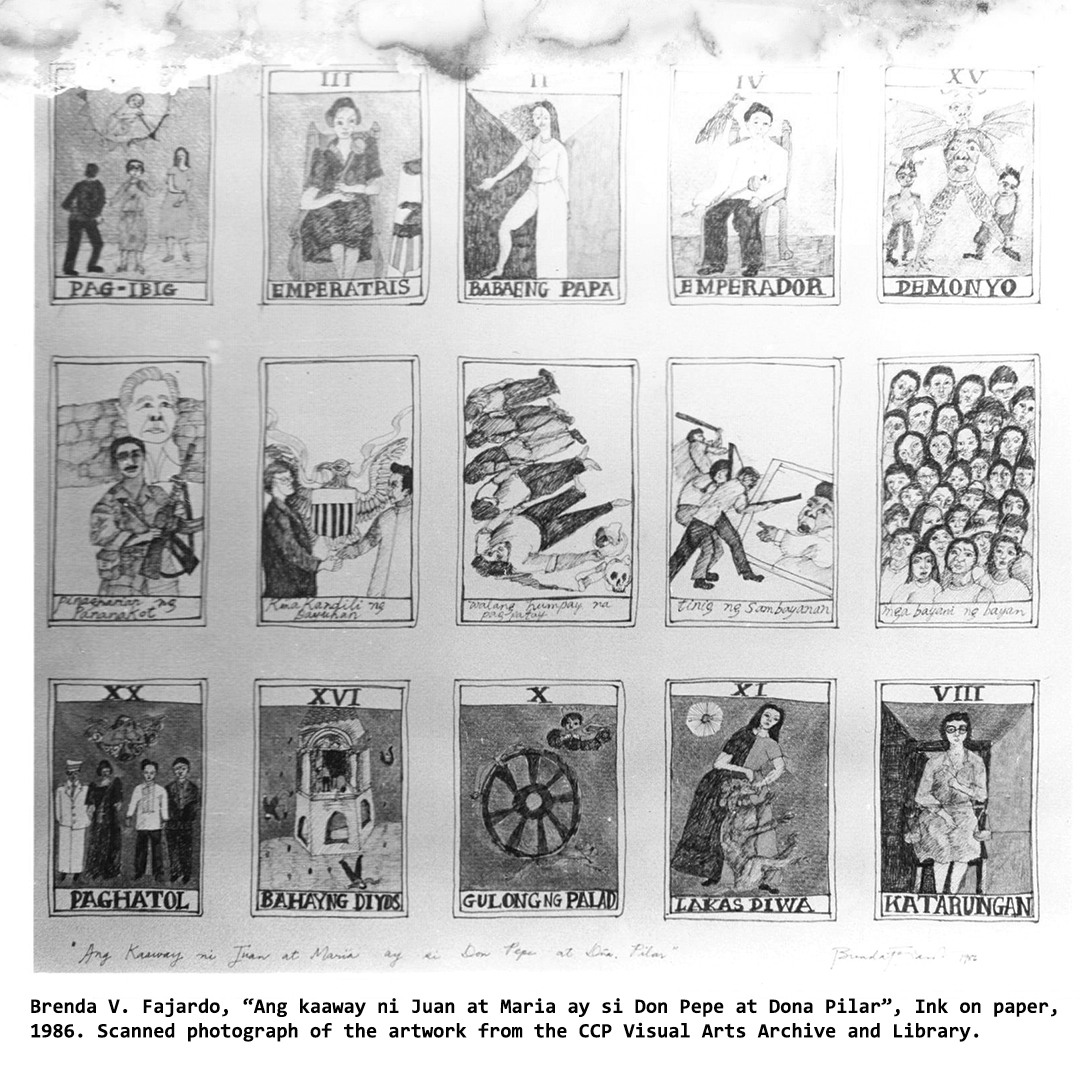

—Brenda V. Fajardo, TAA Year: 1992

Noel Soler Cuizon, Ipinagbiling Kahapon, 1986

Noel Soler Cuizon, Ipinagbiling Kahapon, 1986“I remember hearing the call to head to EDSA via the radio. I was a Fine Arts student then, finishing my thesis, and would always learn about rallies on Ayala Avenue. As a student of a school that supported the Marcoses, we were not allowed to attend rallies as any sighting would mean being called out by the administration. Ironically, my family, especially my father, have never supported the Marcos regime so I always saw the tense atmosphere whether in school or in art. Our concerns in art were about identity politics and making use of indigenous and alternative materials which were separate from politics. I saw the divide and so this heavily influenced my art making. To me, it was about national identity though it was not linear as there were so many catalysts, exposures such as Hiraya Gallery and PETA, and influences like Bob Feleo which transformed the sentiments from the public na na tuloy tuloy na hanggang ngayon. From being an art student in 1986, my perspective now comes as an artist and an art educator that speaks to young artists. Do not think about personalities. Before you produce, you need to know your history, a history that will inform your aesthetics and then will show in your production. After that would be to critique, to have a critical mind, and to be involved. Mahirap kung hindi binabalikan at suriin paano maging involved.”

—Noel Soler Cuizon, TAA Year: 1994

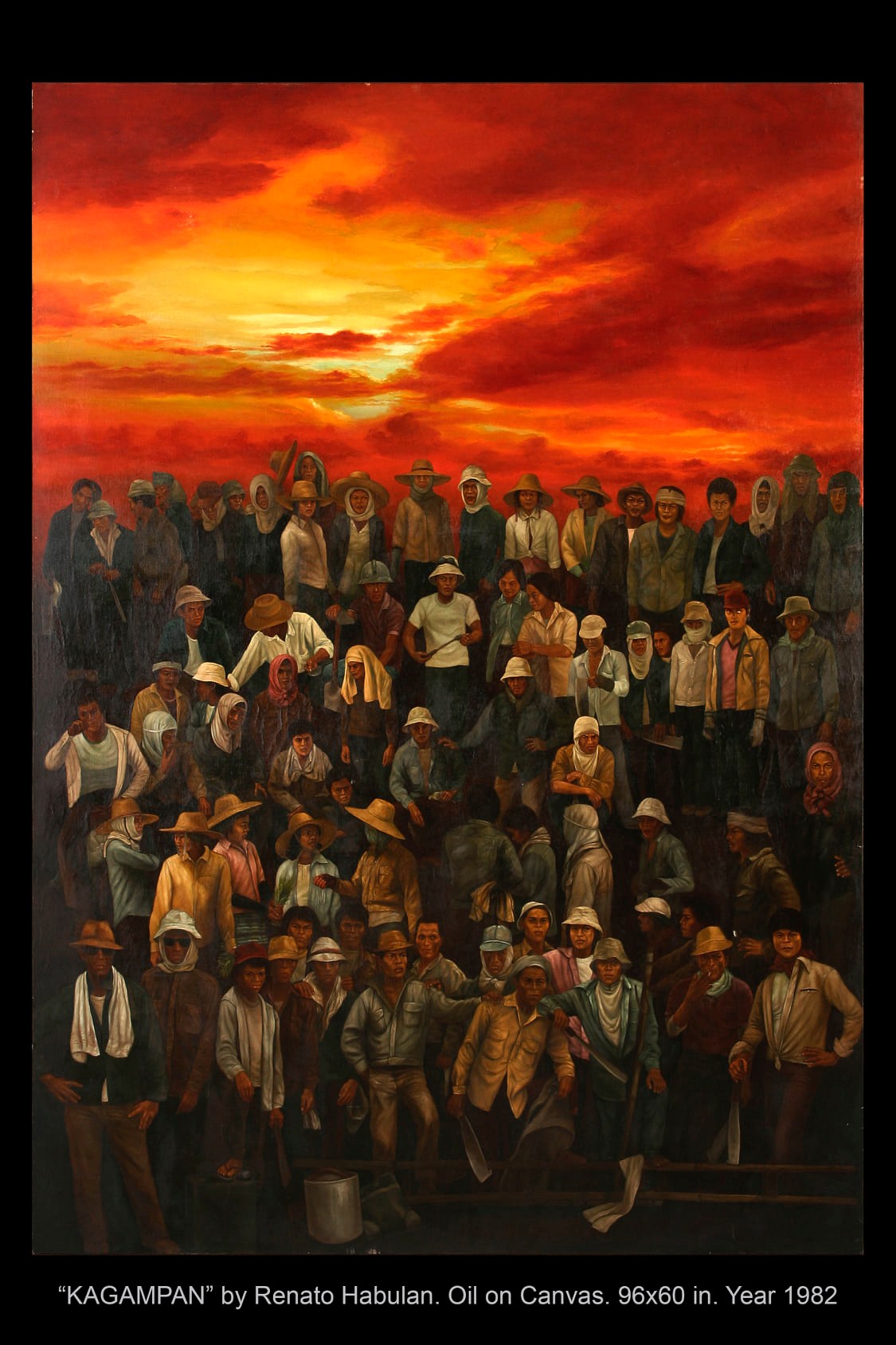

“Sa araw na ito, gusto kong mag-kwento tungkol sa aking journey, yung journey ng mga artist, lalo na ng grupong Kaisahan, during Martial Law na naranasan ko mismo bago mag-1986. Susubukan kong i-kuwento ng objective ito, pero siguro may kaunting romansa dahil ako’y romantic na tao, para sa inyo lalo na kayong mga bata na mag-tutuloy nito. Importanteng magsisimula tayo sa mga firsts, mga unang pangyayari noong Martial Law dahil hindi nangyari [ang 1986 EDSA] ng isang araw lang.

Noong 1977, nagsulat ang Kaisahan ng manifesto na nagpapakita ng pagkakaisa ng grupo na maghanap ng identity in Philippine art, gumawa ng art na nagpapakita ng true conditions ng society. Pagkatapos, noong 1978, importante maalala ang unang rally sa Avenida hanggang Recto kung saan nandoon kami magkakasama. Nagulat nalang kami biglang lumabas ang mga bombero nanagbobomba ng tubig na may kulay. Sa lakas ng hampas ng tubig sa amin lahat nagtumbahan, buti na lang may humarang sa riot pulis noon para makatakas kami. Naka-pula ako noon at ang tubig na may kulay ay para malaman kung sino ang nandoon sa rally. Ang susunod naman dito ay yung first noise barrage pagkatapos ng fraudulent na eleksyon noong April 7,1978 pagkatapos palitan ang konstitusyon. Nagsama-sama kaming mga Kaisahan sa kotse ni Adi [Pablo Baens Santos] at nag-ikot kami mula Sta. Cruz hanggang Quiapo kasama ang mga Center for Advancements of Young Artist (CAYA). Susunod naman sa aking first ay ang first solo ko sa Hiraya gallery na nag-bukas noon August 19, 1983 kung saan ginawa ko ang painting na Kagampan. This gallery space became a watering hole with current news and this exhibition coincided with the rally called Tarlac to tarmac which led to a curtailment in art so I was summoned. Eventually, that was the experience of community and coming together at the time. I felt that as an artist. Last is the Magnificat exhibition in 1985, which was a marian year that showed a trajectory towards spirituality, where Cory Aquino declared her candidacy in the snap elections. For me, art stands on three legs: in form, on content, and with spirit or soul. The spirit and soul would be the metaphysical portion of art. From February 22 to 25, napaka-mobile at napaka-fluid ng development simula ng Cubao. Doon nag-simula dahil sa panawagan. We won the struggle. That peaceful revolution was a model on how to bring about change. We saw that by coming together as a community that we can overcome but now it is scary that we may lose it. We cannot lose this freedom that we struggled to fight for.”

—Renato Habulan, TAA Year: 1990

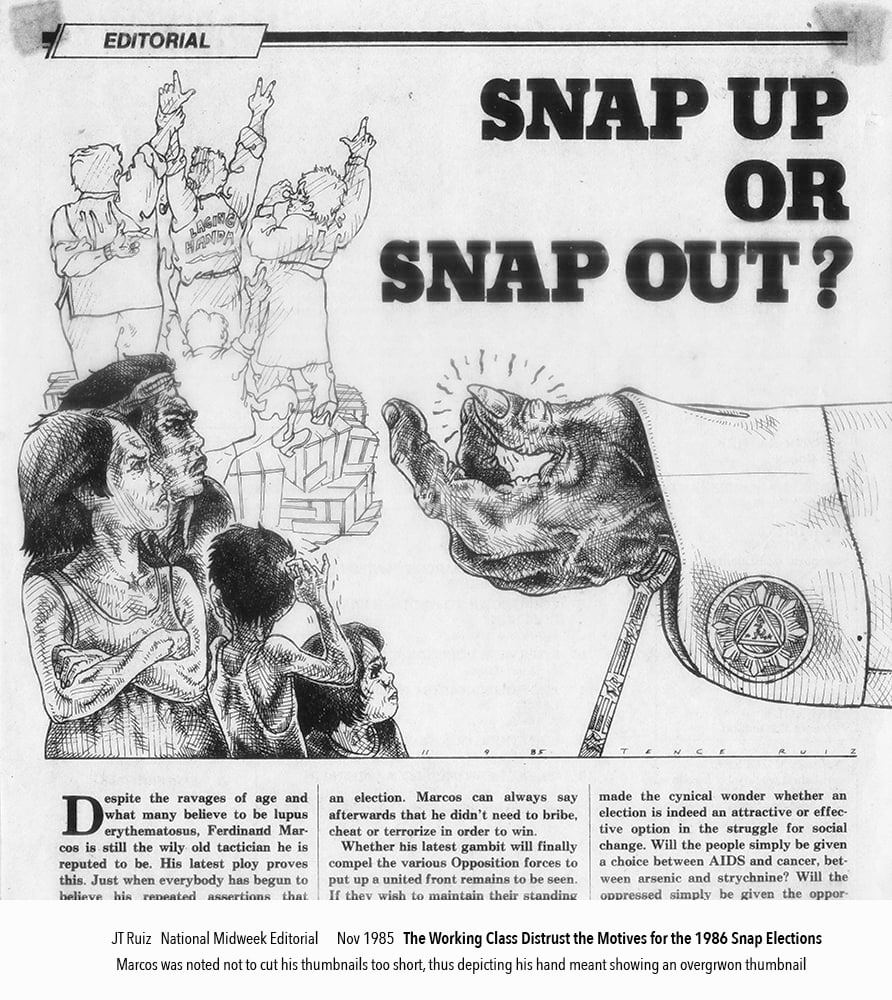

“The Philippines in 1986 was nothing that is different from what it is today. 2022 feels like a replay. People were getting arrested. One of my orgmates, printmaker and painter Manny Gutierrez, was walking out of his house and the next he was seen was on a pile. It was so difficult then dahil bawal at may surveillance lahat sa Metro Manila. We’re talking about Feb. 22 to Feb. 25, 1986. I was working as an editorial cartoonist for The Manila Times, which we revived in time for the February 7, 1986 snap elections. To enter this publication felt both exciting and frightening because for 20 years Marcos did not hold elections he did not control. He had done this in 1965, 1969, and 1981 so there was slight optimism but it would also be dangerous. We never went to work without fear but we had to do it and it was time to do it. It was in our office in Scout Santiago, Quezon city near Roces Avenue where we found out through a small television that [Juan Ponce] Enrile and [Fidel] Ramos decided to go against Marcos and Cory [Aquino] was kept safe somewhere in Cebu. We received the news via radio and telephone calls. It was through the radio that we learned about the call from Cardinal Sin to head outside Camp Aguinaldo and Camp Crame and the attack helicopters sent to disperse the crowd defacted. I share editorials and sketches done while reflecting on the fact that Marcos did not want to accept defeat from the earlier snap election. The self-proclaimed presidency was on the day before he left so when he left there was genuine celebration. EDSA set into motion other things no one expected thirty six years later. Many of the activists of EDSA have become apologists for this government. There were two great lessons that impressed upon me, first is that change does not happen overnight and so you have to be patient and next the point is, second, be consistent with your life. We look at things before, during, and thirty six years later there are so many things to work at.”

—Jose Rence Ruiz, TAA Year: 1988

Phyllis Zaballero, EDSA Noon, EDSA Night, and EDSA Dawn, Triptych, 1986

Phyllis Zaballero, EDSA Noon, EDSA Night, and EDSA Dawn, Triptych, 1986“EDSA was not a rally like the many demonstrations I marched in before which were well-planned and were mounted over the past three years by “militant” groups or organizations.

Rather, it was a spontaneous gathering of anti-Marcos concerned and enraged citizens over a span of three days. We had started hearing about Ramos, Enrile, and members of the military having risen up in revolt against the dictator, President Ferdinand Marcos.They were holed up in Camps Crame and Aguinaldo which flanked EDSA. As news filtered out of this stunning crisis, groups like Butz Aquino’s ATOM started massing nearby. Pivotal to this event, Jaime Cardinal Sin, speaking over June Keithly’s bravely rogue radio station, implored people to go forth, pray outside these camps and protect those sheltering inside. That call from the head of the Catholic church was the spark that inflamed Filipinos to flock to the gates of these military camps even as night was falling.

At about that time, I received an urgent phone call from two of my friends that they were picking me up at home to join the gathering crowd. One was Ching Escaler, a member of AWARE (Alliance of Women for Action Towards Reform) in which we are active members to this day. And the other was our mentor Fr. Joaquin Bernas, SJ.

Off we went to nearby EDSA and saw only a smattering of worried people on the road. This crowd grew exponentially as the hours passed that first night into the next day. The next morning, unable to sleep, I walked alone from my house to EDSA and I was stunned by the number of people baking under the hot sun but not leaving, growing in strength and number throughout the day, into the night until the dawn… when the dreaded helicopters came.

The crowds had been surrounding and pushing against the armored vehicles and tanks which had been sent to forcefully disperse them. The people were using their bodies as shields and linking arms and holding rosaries and statues of the Virgin Mary aloft for the tank crews to see. Some women were climbing the tanks and giving flowers to the soldiers in their turrets. Ultimately, faced by their fellow Filipinos, the men could not obey their brutal orders, they backed away and withdrew.

We had started wearing improvised face masks by then, not the face masks used against today’s Covid pandemic, but alcohol-soaked towels to lessen the effects of the inevitable tear gas, or so we hoped.

It was before light on the morning of the 25th, when my husband,Toti, and I, with our two young sons, David and Guido, and some close friends, among them Sen. Ting Paterno, had stationed ourselves near the gates of Camp Crame. Knowing full well that it would be useless but in quiet despair, there we were in our face masks, gathering stones and debris to build a tank barrier across EDSA, puny as it was. Dazed and sleepy as we were, we just had to do something.

That was when the heartstopping moment happened. We saw the black silhouettes of about seven helicopters swooping down over EDSA out of the dawn sky from the direction of Makati. As these helicopters descended above us, my son David cried out to me, “Mom, their bomb carriages are down and loaded. They’re going to launch missiles.” And we all thought, this is it. THIS IS IT.

They are going to bomb the camps and crowds! I began to pray, to be prepared to die. We were ready to die, all of us. They came down very low right above us and that’s when we realized that the helicopter doors were open and the crews were waving yellow towels and cloths. They were waving at us with these symbols of Ninoy resistance! They were defecting! And then they landed inside the camp. When the crowd saw this, a thunderous roar arose and there was a happiness such as none of us had ever felt before.

It was the unforgettable experience of those three days in our democratic history that propelled me, in a fever of triumph, to start painting my Triptych a few days after. The three works are titled: EDSA Noon, EDSA Night, and EDSA Dawn, 1986.”

—Phyllis Zaballero, TAA Year: 1978

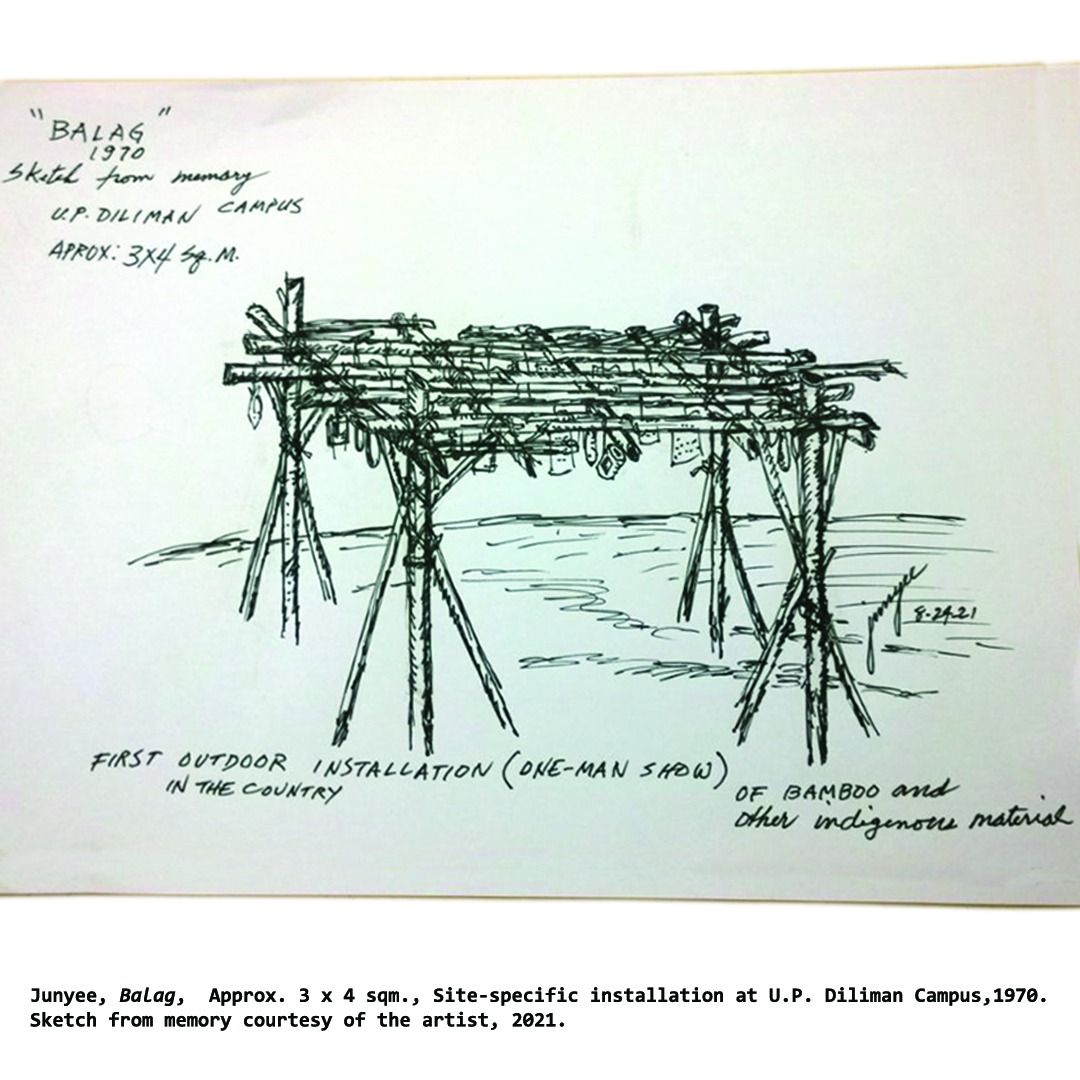

“Balag, my 1970 outdoor installation at UP Diliman, was the first work that expressed anger and opposition to the growing tyranny of the Marcos regime after the First Quarter Storm. The Martial Law period was a really fearful time where many of my classmates were killed. It was not easy for those who were critical of the military rule. That piece, Balag, turned into a space for freedom where I encouraged students to participate in the work. They hung objects, wrote slogans and love poems, and, especially for activists, posted critical statements towards Marcos.

On the second day of the People Power Revolution, this was February 23, 1986, I joined my friends in a borrowed car from UP Los Baños to head to EDSA. It was really celebratory to meet joyful people on the streets, seeing the yellow ribbons tied around, and flashing the laban sign which was a culmination of years of struggle and rallies. That day was the first and only time in my life I’ve ever seen so many people on the street so much so that we had to walk side by side from Guadalupe to Camp Crame. There was a fiesta atmosphere, a joyful day, after many years of pent up emotions towards the government. It was a satisfying relief after years of making installations that criticised authoritarian rule but, right now, I’m sad about our country. After the short-lived euphoric freedom of 1986, darkness feels like it is returning especially today. I’m disappointed to think that many do not know what happened, are not aware of the truth, and have no respect for history. For me, it was a slow process to make art that shared our knowledge as Filipinos and to express our culture. My practice has always been an awareness of the social situation and the state of the environment, and so, I encourage you to be discerning of the facts, to have a sense of nationhood, and a critical mind. For artists, through your art, there is still hope to change the system.”

—Junyee, TAA Year: 1980

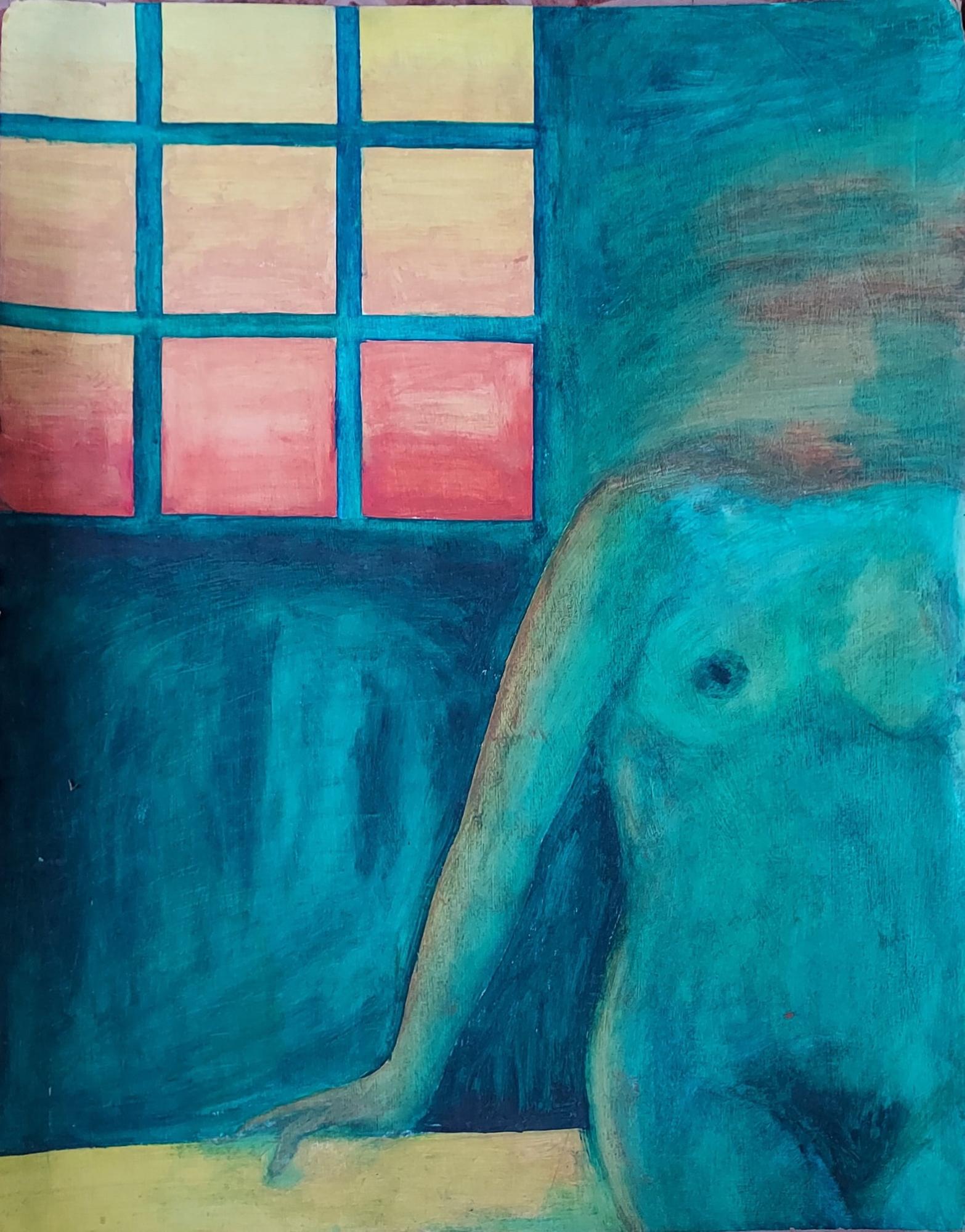

Karen Ocampo Flores, Untitled, Oil on chipboard,1985

Karen Ocampo Flores, Untitled, Oil on chipboard,1985“I have previously refused invitations to speak as an artist of the Martial Law era because I felt that there are more qualified artists who could narrate their own decisive actions at that time. On the last legs of the Marcos dictatorship, I was a student of the UP College of Fine Arts, where for the most part my study of art and my growing awareness about society were not exactly in full sync. I remember talking with other students, and Gemo Tapales remarking that we were a generation that knew no other president our whole lives. “Siya pa rin? Sila lang ba? Marcos pa rin ang susunod?” It was a reality that we didn’t really favor, but we also presumed it was a certainty that was impossible to change.

I started as a freshman in June 1983. By August 21 of the same year, Ninoy Aquino would be assassinated. Along with growing protests, lines also grew for rice or cooking oil. There were instances when we couldn’t buy gas for cooking, so I learned to use charcoal or wood from the backyard. Naturally, art students like me couldn’t buy art materials. A sheet of Ingres paper was only 10 pesos when I started college. By around October it already cost 60 pesos. Many of us resorted to hardware materials, mixing the few tubes of earth tone paints that we have with tinting colors and hubok paste, and painted directly on plywood, not on canvas, with our limited palettes.

We were aware of the social realists. In my high school years, I met Egai Talusan Fernandez and Jose Tence Ruiz at Gallery Genesis, where my late mother Norma Ocampo-Flores used to work. Before this she was with Heritage Art Center where my brothers and I saw critical plays that featured Angie Ferro and Ray Callope Sabio, among other actors.

But UP CFA in the early 1980s was not where you learned about Philippine art history. It was cool to aspire to be “New York” via Art Forum or ARTnews, and not to be “Nativist” in the pursuit of Filipino themes. We had so much difficulty reconciling art with politics, much less with the realities that we dealt with in our own lives. It would be an informal dictum, going with Roberto Chabet, one of our teachers, that to have no statement was the best statement to have with one’s artwork.

My father, the writer previously known as Jaime Maidan Flores, was an official of the Marcos government until around the 1980s. My late grandfather HR Ocampo counted Imelda Marcos as an important patron and credited her for ushering in an art market boom by the 1970s. Nonetheless, it was my Mama who warned us early on as kids to be careful with our words, telling us that “the walls have ears.”

My brothers, the twins Oliver and Percival went to UP Integrated School, and it was through them that we learned about history and politics in our adolescence. Elections for the Interim Batasang Pambansa (National Assembly) were held in 1978, and we tried to do our part on the street, drawing our sort of editorial cartoons and pasting them on concrete walls as we waited for the noise barrage called by Laban (Lakas ng Bayan).

We moved to Quezon City in 1979, after my grandfather died the previous year. And when Snap Elections were called on February 7, 1986, my brothers and I volunteered at Radyo Veritas during the counting period to help with the broadcast of elections news, in contrast with the official news disseminated by government-controlled media. The declaration of Marcos as winner prompted a spate of protests. We watched Cory Aquino’s call for a boycott of crony-owned businesses at the Luneta Park. Civil resistance kept building until the last week of that February.

On February 22, I was one of the UP CFA students featured in Young Art, a group show organized by the Cultural Center of the Philippines. It was opening night. Elmer Borlongan and Mark Justiniani were also there. Mark rode with us going home and we were surprised to see a crowd building in Camp Crame in EDSA. We turned on the radio and heard Juan Ponce Enrile’s “confession.” General Fidel Ramos was also speaking beside him. That evening, my brothers and I did not proceed to EDSA. We joined the crowd that amassed at Radyo Veritas. But by dawn the next day, February 23, government forces already destroyed the station’s transmitter in Bulacan. By 12:00AM of February 24, June Keithley moved the broadcast to DZRJ in Sta. Mesa, Manila as Radyo Bandido. That same morning, my brother Percival and I were part of the Radyo Veritas crowd that rushed to MBS Channel 4. We all thought that the anti-Marcos Reformist soldiers had already taken over. But we were met with hostile gunfire. That was a memorable run for us.

I remember taking a much-needed nap right after reaching home. Past lunchtime, we tuned in to Channel 4, and it was just breathtaking to see June Keithley and other personalities speaking from a studio right there. The next day, February 25, we proudly viewed the telecast of the inauguration of Cory Aquino and Salvador Laurel at Club Filipino.

The Snap Elections and EDSA People Power of 1986 were catalysts too for my own resolve to venture into leadership as an artist. That same year, I joined UP Artists Circle and under SAMASA I ran for College Representative of UP CFA and sat with Chair Kiko Pangilinan and other elected members of the University Student Council. Before graduation, I was accepted as a writer for Radio-Television Malacanang. One of my tasks was to write scripts for President Cory Aquino’s Magtanong sa Pangulo with the late Orly Punzalan as host. In my art, I pursued a social realism that centered on the feminine body as culturally contested ground. Then I entered motherhood in the 1990s while collaborating in critical murals with Salingpusa and Sanggawa.

I hope that my story could impart to students of arts and design today how they should be confident of their social role and leadership as creatives. The lessons of Martial Law should be addressed first in utmost empathy with the people who suffered and died under the rule of the Marcoses. How they ruled was and is still largely through the manipulation of minds; hence, culture and art remain their weapons of mass inculcation. We must see and present truths beyond the convenient lines drawn by political personalities.”

—Karen Ocampo Flores, TAA Year: 2000